In 1836, Henry Spalding and his wife Eliza joined Marcus and Narcissa Whitman on a mission to the Oregon Country. In 1846, Spalding acquired Nez Perce clothing, artifacts, and horse gear which he shipped to his friend and supporter, Dr. Dudley Allen, in Ohio. Dr. Allen wrote to Henry Spalding on March 27, 1848 that the box containing this saddle was badly damaged.In exchange for these Native American goods, Dr. Allen, a benefactor to the Presbyterian mission sent needed commodities to Spalding. After Allen's death, his son, Dudley, donated the Spalding-Allen Collection to Oberlin College in 1893. Oberlin College in turn loaned most, but not all, of the collection to the Ohio Historical Society (OHS) for safe keeping where it languished for decades.

In 1976, curators at Nez Perce National Historic Park (NEPE) rediscovered the collection. After negotiations, OHS loaned most of the Spalding-Allen artifacts to the National Park Service in 1980 on renewable one year loans. However, in 1993 OHS abruptly demanded the return of the collection. In negotiations with OHS, the National Park Service learned that OHS would sell the collection, but only at its full appraised value of $608,100 with a six month deadline to provide the money. The Nez Perce Tribe raised the money within six months with help from thousands of donors and purchased the collection where it is now on loan to NPS.

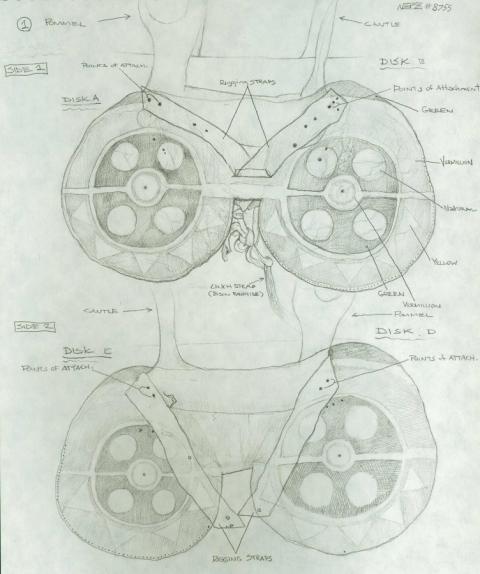

A decorated Nez Perce woman's saddle made circa 1830-1845 with cotton wood frame and painted geometric designs on the fenders from the Spalding-Allen Collection. Bison hide tie laces secure the rawhide inner pieces forming the pommel.

L 60 x W 32 CM back; 27 width front; 38.5 height fenders 76 x 43 CM (approximately).

Nakia Williamson-Cloud describes the labor involved in making this saddle:

[scald=60:sdl_editor_representation]

"Saddle making is primarily a man’s sort of endeavor. But that was somewhat different for our tribe, at least in this situation, because this was a type of saddle that was utilized by women and girls. And from my understanding, these saddles were made by the women. There were certain women that obviously excelled at this, making these sorts of items. But I think it was a fairly widespread kind of necessity at that time. You know, everything that our people utilized was pretty much made by the people themselves. And I don't know if there were necessarily specialists, like there were in other communities where certain people specialized in being blacksmiths or specialized, you know. I think there were people that were probably excelled. But that all people had a lot of this type of knowledge to take care of their own lives.

And so a lot of the women, I think, obviously the hide, the fenders, and I’m not sure about the rawhide, I don't know, but I know a lot of the rawhide that’s part of the fenders and part of the rigging is made out of buffalo hide. Which, for the most part, would have been hunted by men, obviously, more than likely in what is now Montana/Wyoming plains. There were buffalo on the west side of the mountains. And our oral histories do talk about buffalo being on this side of the mountains. And then even as early as probably the 1700s they were hunting them on the Snake River Plain and some of those areas. You know, so the hide would have been hunted by the men.

But a lot of the hide work and things of that nature was done primarily by the women, simply because they were the experts at that. And they would have more likely harvested the cottonwood utilized for their frame, you know, here locally or wherever they might have been when they were putting together this item. And it’s sewn together with solid pieces. It’s similar to the way western saddle making is, where the pieces are sewn together around a frame. But I think the difference is they use sinew to sew all the rawhide on. Then it was formed. Then it slowly, basically, dried and shrank and made that combination of the cottonwood and the rawhide made it a very sturdy sort of structure to, basis for the rawhide.

And the fenders were painted with various types of, I think most of them were earth pigments. I’m not sure what the analysis was. But a lot of them are consistent with what would have been found locally or within the areas where they could trade various types of colored pigments."

Kevin Peters on how this is a Cadillac of saddles:

[scald=61:sdl_editor_representation]

"This is a Cadillac. And I’ve always kind of found that funny is that some of the elder women like to have a big car. And my aunty had her big car. And they would go berry pick, her and her friend, and you’d see all their bags in the back. And off they would go. And it was one of the things where she told me one day about being stuck up on a hill. And as they rounded the corner, it was a hairpin corner, a landslide came down. Covered the road on the top of the corner and the bottom, and they were trapped in between. And then she told me, “This is the reason why we have road food when you take a trip.” She said, “We were stuck there for six hours. We had everything we needed. We had food, water and toilet paper. And we had two big seats we could rest on.”

And it was like, okay, I kind of see a reason for having a big car. You know, this was their horse at the time. That was probably back in the late ‘50s, early ‘60s, that happened. But it was kind of interesting to see that because the woman controlled the household goods and it was her ability to move everything, that they would do it in style. It wasn’t just, “Okay, let’s hop on the horse and go.” No, we’re going to do it and look good doing it. That way, you all get together and you say, this is who we are. Even we’re moving, you’re making a statement. And that’s what I found out about these was that there are other pieces, like the fenders. And this being one of the only fendered Native American saddles in America. But the fenders are a construction of rawhide and painted, and probably had beadwork around the edges from all the little holes I can see on it, or maybe had a wrapping of cloth around the edge of it.

Around the world in other museums, I don't know, there are five or six other pieces that are fenders that look like these. I mean, just about identical. So somebody was making a statement at some point in time, in a group, that said this is who we are. And I find them beautiful. I mean, it’s just an amazing saddle. I’m amazed we still have it. But it’s just quite beautiful. It’s a piece of artwork. It’s a very three-dimensional piece of work that just looks, you know, that would look good hanging just being by itself, it’s beautiful. Doesn’t even need a horse underneath it."

Saddle located at the Nez Perce National Historical Park.